Starry Skies & Phthalo Seas (An Introduction to the Works of H.P Lovecraft, Part 1)

A brief look at Lovecraft's influence, why people are turned off by his works, and serving as a bridge to Part 2, where I provide story recommendations and my reasons for looking into them.

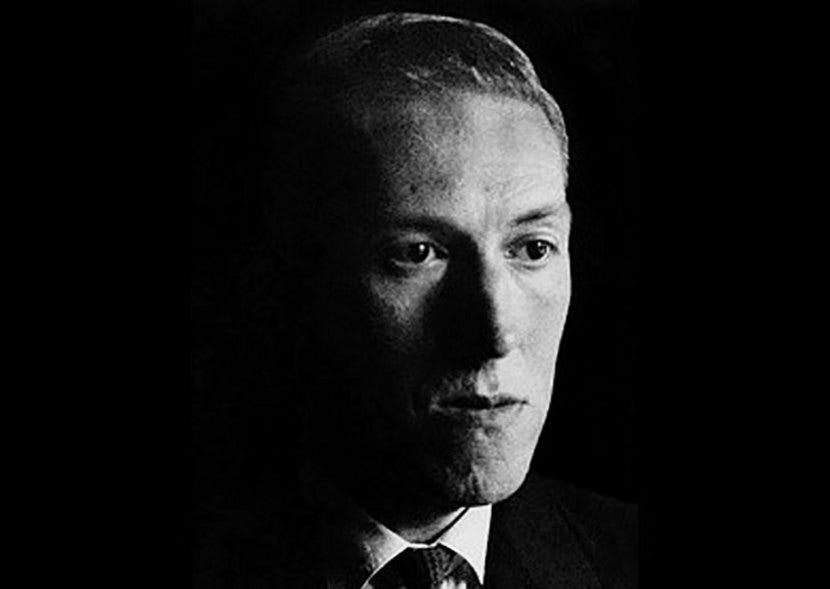

The name Howard Phillips Lovecraft, or as he is most commonly known; H.P Lovecraft, is as ubiquitous as the name of his most famous monster Cthulhu. The two have become so synonymous that Lovecraft, himself has been cheekily included into his own pantheon of extraterrestrial gods; his visage and supposed misanthropic, reclusive personality being used in stories, memes, and as the personified poster child of cosmic horror pop culture. His legacy in American horror fiction is indisputable, praised and hailed by icons such as Stephen King, Clive Barker, Guillermo del Toro, Robert Bloch, Neil Gaiman, Thomas Ligotti, and many more. His and other contributor’s collection of writings, also known as the Cthulhu Mythos, is perhaps one of the most influential collected works of the 20th and 21st century, long having been used as a framework for other author’s supernatural horror fiction. His works have spawned many imitators, comic books, film adaptations, video and tabletop roleplaying games, brew pubs (R.I.P the Lovecraft Bar of SE PDX and LoveCraft Brewing of Bremerton, WA), and is even the focus of two popular film festivals in Portland, OR and Providence, RI. Suffice to say, the man has left a significant legacy, made even more impressive by the fact that by the time he had succumbed to cancer of the small intestine at the young age of 46, he was virtually unknown outside of a small, tight-knit writer’s circle of fellow pulp magazine authors and a handful of correspondences whom he passionately mentored.

However, despite his celebrity status in modern horror, and being known by name by anyone who’s ever glanced through the horror section of a bookstore, or played a TTRPG, or have just heard any of the names of Lovecraft’s equally famed Great Old Ones, I have long been surprised by the amount of people who claim to be Cthulhu Mythos fans without having ever actually read any of the stories. When asking these people why they haven’t read Lovecraft despite claiming to be a fan of his, the usual response to my query is “I just haven’t gotten around to it.” Though this statement is both vague and simplistic, I have a few postulations on what it actually means, and why a lot of Lovecraft fans have not read his work:

The antiquated writing style. Lovecraft was deeply fond of purple prose. While not entirely uncommon for this time period, Lovecraft differentiated himself by eschewing the slang and gradual modernization that was growing more popular in American fiction, instead writing in an archaic style commonly associated with the nineteenth-century British aristocracy. Lovecraft fancied himself as an educated man with well-off Anglican ancestry, choosing to spell particular words in their British English forms rather than American English. E.g The Colour out of Space instead of The Color out of Space. Other adjectives I’ve commonly heard used by people who have read and disliked Lovecraft, or have skimmed from a book of Lovecraft’s short stories, include “Pretentious”, “Dry”, “Academic”, and “Boring”. These can be understandable if one is not accustomed to reading this type of literature, but I shall elaborate on Part 2 how one can acclimate themselves to Lovecraft’s style of writing, and grow to appreciate and enjoy it.

Not knowing where to start. Though it’s commonly stated the Lovecraft has only 52 short stories in his repertoire, if you also count the stories that were published posthumously or that he ghost-wrote for/with other writers, including works that haven’t been published in physical copies for several decades, the number climbs up to as many as 120. What complicates this even more is that most of Lovecraft’s tales are usually interconnected in some way, often referencing characters, timelines, and plots that can come off as confusing to a reader who’s picking it up for the first time. Despite the vague timeline, I would like to point out that Lovecraft would often put the names of Great Old Ones in his works not because they were necessarily relevant to the plot, but as a homage to authors whom he was influenced by (such as Hastur being referenced in The Whisperer in Darkness, a character that originally first appeared in Ambrose Bierce’s Haïta the Shepherd), or in a jocular way of referencing a creation made by one of his friends in his writing circle. If one is looking to get into the Mythos from the very beginning, it’s actually relatively easy to find a starting point and move on chronologically from there, which I shall elaborate on further in Part 2. I would also like to mention that Lovecraft’s works can be enjoyed no matter what one starts with, or if you just decide to read one of his stories.

Reading the works of an author influenced by Lovecraft’s Mythos, only to try Lovecraft and find that it’s completely different from what you were expecting. This was a very common problem friends of mine were having when trying to get into H.P Lovecraft, and it would not surprise me if many others have run into this. The reason for this is complicated, but I can at least pinpoint an origin on where the confusion began. Shortly after H.P Lovecraft passed away in 1937, his good friend and fellow writer August Derleth started up a publishing company called Arkham House to keep Lovecraft’s and other pulp writer’s obscure works continuously in print. Whilst we owe Derleth for keeping Lovecraft relevant and promoting his works, a rather insidious aspect of Derleth’s character came out alongside the re-publishing of his friend’s stories. He began asserting legal control over all of Lovecraft’s work, which he technically did not have the power to do, as Lovecraft kept his works in the public domain for other writers to contribute to. Along with this, Derleth began reworking and restructuring the Cthulhu Mythos, even coining this term (Lovecraft preferred to call his collection of works Yog-Sothothery), and (in my opinion, deliberately) misunderstanding the Mythos to the point where he posthumously published Lovecraft’s incomplete short stories and inserted his own flawed interpretations into them, including: the good-vs-evil debacle of the Great Old Ones and the Elder Gods, the Great Old Ones being assigned to one of the five classical elements of Ancient Greek cosmology, constructing a genealogy line for the Old Ones (with plenty of sibling rivalry!), and having the Great Old Ones acting on more capricious whims in manners similar to Ancient Greek deities. What you are believing to be based on Lovecraft’s own works, which is based on pop culture, usually stems on the plagiarism and misconceptions of Derleth, who has left a permanent mark on the modern Mythos. Lovecraft never once uses the concepts of human morality for the Old Ones in his writing, nor did he reference the elements, nor did he humanize his alien gods (aside from a notable example, Nyarlothotep). Second-generation Mythos writers of the later 20th century, would further embed their Lovecraft-inspired novels with Derlethian Mythos constructs, thus muddying the waters further. This leads to a lot of confusion and disconnect by fans of Lovecraft’s tales, people who wish to get into Lovecraft, and those who partake in media supposedly influenced by Lovecraft. This is a surprisingly complicated topic, one which I shall cover further in a future post called The Expunging of August Derleth.

Though there are most likely several other reasons why many people have not read Lovecraft’s short stories, the three I have listed above, based on what I have heard from my friends and from various posts of social media, are perhaps the biggest contributors for the disparity between Lovecraft’s literature and the culture inspired by his work. For those who are looking to go back to the roots of cosmic horror, enjoying its beauty and slow-simmering otherworldly terror, and looking for a fresh start, this is the place for you.

In Part II, I will be giving my personal recommendations on where to start with Lovecraft for the aspiring beginner reader of his works, getting accustomed to his prose, and working your way from there. Though Lovecraft’s most popular work was published in the late 1920’s to the mid 1930’s, we will be starting much earlier than that, going all the way back to a short story Lovecraft wrote back in 1905, when he was just 15 years old. This is where his Mythos truly began, and from here we will make our way through various other works of his, both seminal to highly obscure, with explorations of overarching themes and archetypes. Links to free digital versions of his stories will be linked, though I highly recommend purchasing a complete Unabridged Version of his tales. My goal by the end of this series is to gain a new appreciation for this seminal author, and to realize that his prose is not only more digestible that you think, but also very enjoyable to read!

In Part III, we will be going over the works that influenced Lovecraft, himself, including authors such as Lord Dunsay, Edgar Allen Poe, Ambrose Bierce, Arthur Machen, Robert W. Chambers, and several others.

I look forward to diving into the literary depths with you all.

Until then, bonum noctis, et mare ditat.

Adding to the discussion on his prose—I was discussing this with another writer. It’s not JUST purple prose. The way sentences are structured… the reader gets to uncover and notice the environment along with the narrator. It’s a subtle but significant difference between more modern scene-setting!

This is such a great breakdown! I think mountains of madness is my favorite. I’m currently working through his complete unabridged works