The Legacy of Lovecraft: How the Mythos Emerged from the Shadows, Part II

The complicated and controversial background of a pulp author's rise to fame, part 2.

Originally, I had anticipated being able to cram enough information about Derleth and Arkham House in Part II all the way up to the time period of the 1970’s, but researching this topic to such extraordinary lengths instead lead me down a complete rabbit hole that was just too enticing to ignore, and not covering it would have been a great disservice to the now long-forgotten people who helped give Lovecraft exposure.

Without further ado, welcome to Part II of this deep dive. If this is your first time here, I highly recommending reading Part I before proceeding, though I will also do my best to summarize it below as a recap for returning readers.

In Part I, I introduced you all to August Derleth, a friend of Lovecraft’s whom after the author’s death, would found Arkham House (along with a fellow friend Donald Andrew Wandrei) to keep Lovecraft’s works in print. Despite his good intention to expose his friend to a wider audience, I mentioned that Derleth would make some very unusual decisions that would later sour his legacy amongst fans of Lovecraft. I went into one of the most impactful choices he made, which was his poor treatment of Robert Barlow, Lovecraft’s 18-year-old protege and assigned literary executor by Lovecraft, himself. Derleth repeatedly lied to Barlow about his lack of legal rights of being a literary executor. Along with this, Derleth would make slanderous remarks about Barlow’s homosexuality to writers in the pulp writing circle whom Lovecraft had been deeply connected to. This resulted in Barlow being shunned, even after he had signed away his executor rights to Derleth. Barlow would go on to teach Mesoamerican History in Mexico, where he was lauded by his peers, but due to a combination of persistent depression and a fear that his homosexuality would be exposed by a disgruntled student, he would commit suicide at the age of 32. Though he died young and estranged, his donations to Brown University of Lovecraft’s letters and manuscripts, as well as the discovery of his transcript of Lovecraft’s original edition of The Shadow out of Time, would later cement him as a well-respected figure in the Lovecraft scholarly scene.

This is where we left off in Part I. In this article, we will be focusing more on August Derleth’s role as Lovecraft’s successor, as well as the start of the preservation and honoring of Lovecraft in early fanzines.

Though we don’t have an exact date as to when Robert Barlow resigned his executorship to August Derleth, we do know that it occurred between the Spring of 1937 and the Summer of 193812, in which case Barlow would have been no older than 20 years old. Exhausted and freshly castigated from the pulp writing scene by Derleth’s own doing, the young Barlow would permanently leave the East Coast to study Anthropology out West.

Derleth, now the freshly-minted literary executor of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, would without doubt feel victorious over his new role. Thus would begin Derleth’s gradual control of Lovecraft’s legacy.

The Origin of the Cthulhu Mythos

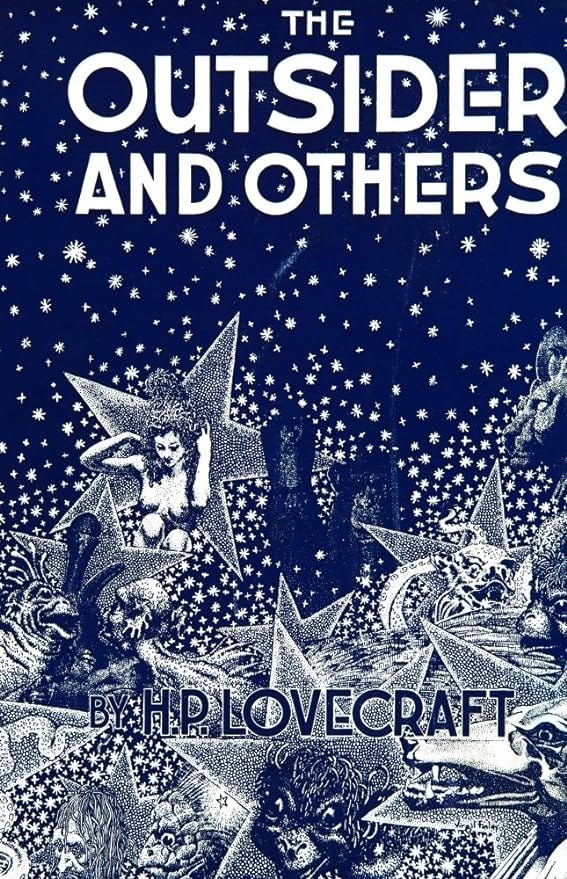

1939 would end up becoming a very productive year for August Derleth. This would not only be the year he would found Arkham House and publish the very first hardback collection of Lovecraft’s short stories The Outsider & Others, it would also be the year he would publish The Return of Hastur.

You might be wondering what this particular short story has to do with anything we’re going to be talking about, or what this story even is. As obscure as The Return of Hastur has become nowadays, it would serve as a connection to what Lovecraft, himself had written and what Derleth would establish into the organized Mythos many of us have come to be familiar with.

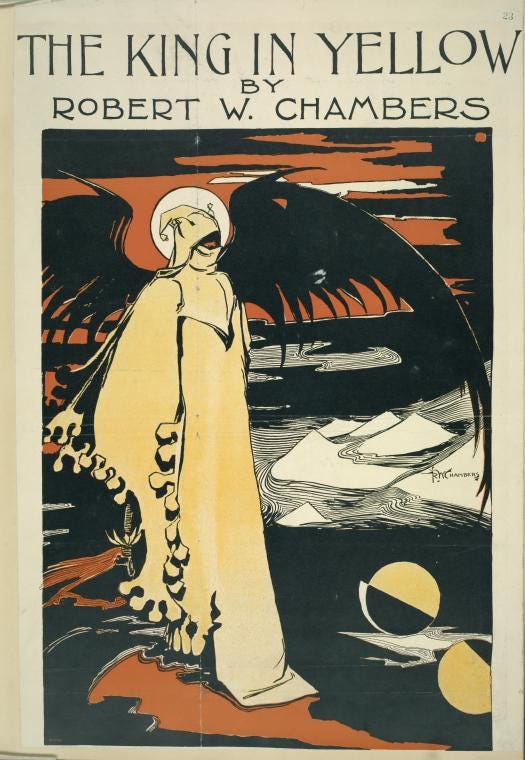

Derleth, for some particular reason, was fascinated by the deity Hastur and the affiliated alien-city of Carcosa. Originally created by American author Ambrose Bierce, Hastur and Carcosa would later be featured within a famous collection of short stories monikered The King in Yellow, written by Robert W. Chambers in 1895. Hastur would also be referenced in fiction by Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany. Lovecraft, who was deeply influenced by all these authors, would briefly mention Hastur in his 1930 short story The Whisperer in Darkness:

“I found myself faced by names and terms that I had heard elsewhere in the most hideous of connections—Yuggoth, Great Cthulhu, Tsathoggua, Yog-Sothoth, R’lyeh, Nyarlathotep, Azathoth, Hastur, Yian, Leng, the Lake of Hali3, Bethmora, the Yellow Sign4, L'mur-Kathulos, Bran and the Magnum Immonandium…”

It should be noted that Lovecraft, in the quote above, lists not only names of fictional entities, but places as well, and does not elaborate in this context on whether Hastur is a character, a place, a deity, or an object.

Derleth would approach Lovecraft years later, looking to decide upon a collective name that would encompass Lovecraft’s and other contributor’s works of fiction. Lovecraft, years back, had originally coined the term “Yog-Sothothery” to suit the purpose, though the phrase was most likely meant to be jocular, having written in a 1931 letter to fellow writer friend Frank Belknap-Long: “I really agree that Yog-Sothoth is a basically immature conception, & unfitted for really serious literature…”5. On rarer occurrences, Lovecraft used the term “Arkham Cycle” to refer to the vague interconnection within his stories based on his fictional town of the same name6. “Cthulhuism” was also used by Lovecraft sporadically in letters to friends7.

The moniker Derleth originally suggested was “The Mythology of Hastur”, which Lovecraft politely rejected, pointing out that Hastur was not his original creation8, a fact compounded with Lovecraft mentioning the name only once, as a throwaway reference, in his entire corpus. It was only after Lovecraft passed away did Derleth create and settle with the title Cthulhu Mythos9, which would become the official term for Lovecraft’s fictional mythology, particularly from tales Lovecraft wrote in the last decade of his life. Though the name works well when explaining references found scattered across Lovecraft’s fiction, as well as those in the pulp writing circle who referenced Lovecraft’s concepts and vice-versa, it would also be used entirely in Derleth’s favor.

Following Lovecraft’s death, August Derleth conversed with Harold Farnese, a composer who, in 1932, either before or after setting two of Lovecraft’s thirty-six sonnets from Fungi from Yuggoth to music and performing them10, had corresponded with Lovecraft in a couple letters and a postcard, with Farnese querying about the author’s theological beliefs and the use of such concepts in his weird fiction. Derleth requested Farnese to locate the letters to be used for his influence, as well as having an interest in publishing Lovecraft’s personal letters. Though Farnese never supplemented these to Derleth, the composer would instead send Derleth second-hand recollection from the letters, in which he claimed Lovecraft had supposedly written the following:

“You will, of course, realize that all my stories, unconnected as they may be, are based on one fundamental lore or legend: that this world was inhabited at one time by another race, who in practicing black magic, lost their foothold and were expelled, yet love [sic] on outside ever ready to take possession of this earth again.”11

These letters have never been located in their entirety, and quotes of similar nature cannot be attributed to Lovecraft12, though fragments of the letters have been discovered and published, in which Lovecraft had once written to Farnese:

In my own efforts to crystallise this spaceward outreaching, I try to utilise as many as possible of the elements which have, under earlier mental and emotional conditions, given man a symbolic feeling of the unreal, the ethereal, & the mystical – choosing those least attacked by the realistic mental and emotional conditions of the present. Darkness – sunset – dreams – mists – fever – madness – the tomb – the hills – the sea – the sky – the wind – all these, and many other things have seemed to me to retain a certain imaginative potency despite our actual scientific analyses of them. Accordingly I have tried to weave them into a kind of shadowy phantasmagoria which may have the same sort of vague coherence as a cycle of traditional myth or legend – with nebulous backgrounds of Elder Forces & transgalactic entities which lurk about this infinitesimal planet, (& of course about others as well), establishing outposts thereon, & occasionally brushing aside other accidental forces of life (like human beings) in order to take up full habitation… Having formed a cosmic pantheon, it remains for the fantaisiste [sic] to link this “outside” element to the earth in a suitably dramatic & convincing fashion.13

This is the closest scholars have located of Lovecraft saying anything remotely resembling Farnese’s “Black Magic” paraphrase. Derleth would, however, immediately take Farnese’s paraphrasing as gospel. It is unknown whether he actually believed that this was Lovecraft’s exact wording, or if he went along with it because, as Derleth was a firm Christian, it aligned perfectly with his own dogmatic interpretation of the Mythos. Whichever one it may have been, it was enough for Derleth to label as being canonical, and it is from here that the Cthulhu Mythos would begin to take shape.

A note of interest I would like to bring up, before wrapping up this section, is that Harold Farnese would compose and perform a two-page piano solo called An Elegy for Lovecraft, which he wrote in 1937 shortly after the author’s death. He would not be the only musician to do so. That same year, writer and composer Albert Galpin, who had been mentored as a teenager by Lovecraft, would also pen a piano piece, called Lament for H.P.L14. The original sheet music for An Elegy for Lovecraft can be viewed through the Brown University Digital Repository here, whilst a truly wonderful rendition of Lament for H.P.L can be listened to here, on behalf of the H.P Lovecraft Historical Society. The more you know!

The Derlethian Mythos

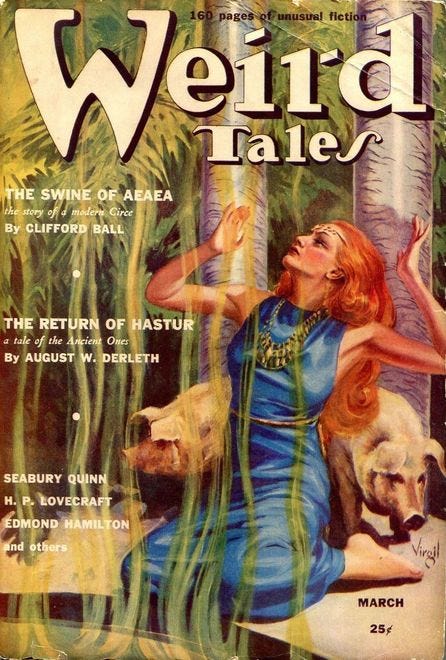

Derleth began penning The Return of Hastur in 1936. Lovecraft is rumored to have read it, though his thoughts on it are at this time not known. Derleth would send a draft of the tale to pulp writer and close friend of Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, in 1937, merely looking for positive reception. What Derleth received back instead, was an amicable, albeit bemused letter from Smith, who gave a complete list of advice that would have inevitably benefitted the story in the long run, however Derleth would unfortunately disregard Smith’s advice15, and proceed to send his completed version of the story later that year to Weird Tales. It would be published in the magazine in March of 1939.

What makes The Return of Hastur a particular notorious story is not only its dubious writing quality (I will not go into the plot in this deep-dive, as I will be doing a review of it in the near future), but rather its establishment of ideas which Derleth would attempt to claim as being part of Lovecraft’s original vision, concepts that are now as infamous as they are ubiquitous. This story would introduce:

The hierarchy of the Great Old Ones.

Whilst the term “Great Old Ones” was originally introduced by Lovecraft, first appearing in The Call of Cthulhu to describe Cthulhu, himself, it was less of a classification and more of a vague moniker; as Lovecraft would also use the term ‘Great Old Ones’ in reference to the Elder Things in ‘At the Mountains of Madness’, though the Elder Things are never classified as imprisoned gods by Derleth.

The concept of Lovecraft’s gods sharing genealogy is based on parodical family trees Lovecraft would construct with his friend Clark Ashton Smith and later, Robert Barlow16

(seriously, Lovecraft was a bigger goofball than people give him credit for and his wryness was often taken too seriously), but he never explicitly incorporated this into his fiction.The establishment of a moral conflict between the evil Great Old Ones and the benevolent, humanoid Elder Gods.

The Great Old Ones in Derleth’s mythology being the deities Lovecraft would use in his own stories, such as Shub-Niggurath, Cthulhu, Tsathoggua, etc., however Lovecraft never associated these creatures as being “evil”, but instead aloof to humans and at worst, morally neutral. The Elder Gods, whilst a name that traces back to Clark Ashton Smith, are entirely a Derlethian creation in the vein of them being a class of benign deities intent on saving the human race from the Great Old Ones who wish to subjugate us. The Elder Gods and Great Old Ones are meant to appear analogous to the Christian belief of Satan and fellow fallen angels being cast from Heaven, with the Elder Gods even said to be residing in a realm called ‘Elysia’, or ‘Heaven’ in Latin. This is a particularly troubling correlation on Derleth’s behalf, as Lovecraft was openly averse to the Abrahamic faiths (and religion in general) and portrayed his worlds as amoral and abstract.

The Elder Gods being the ones who imprisoned the Great Old Ones Interestingly, there are no references to any gods outside of Cthulhu being imprisoned in Lovecraft’s stories. While this does not mean that other Great Old Ones could not be imprisoned themselves, it would be a significant stretch for all of them to be so, as gods such as Nyarlathotep, in Lovecraft’s fiction, are free to walk the Earth (in various avatars) as he so pleases.

The “elemental theory” for the Great Old Ones

By far one of Derleth’s most peculiar additions. According to Derleth, each of the Great Old Ones align with one of the four elements ascribed in Ancient Greek philosophy: Fire, Water, Earth, and Air. He establishes this as being a fundamental reason for why certain Great Old Ones have antagonistic relationships with each other, citing that Hastur (who, according to Derleth, is Cthulhu’s half-brother and is now specified as being a physical entity) is an Air elemental and Cthulhu a Water elemental, which he claims naturally contradict each other.

Not only does this have absolutely no ties to remotely anything Lovecraft would describe in his stories, but it is also very much Anti-Lovecraft. Assigning alien gods to the Aristotelian idea of the four elements is essentially humanizing the complex and unknown; the “Classical Elements” theory was a simplistic concept that was used to explain how each of these elements made up the universe, before the advent of the scientific method in the 18th century. Derleth is attempting to rationalize what Lovecraft wrote as being beyond human understanding, and using laughably outdated notions to do so.

Derleth hits hard with all of these principles, which he firmly wants us, the readers, to take for granted. Whilst characters in Lovecraft’s stories will refer to these alien entities as “malignant”, the individuals who are usually proclaiming such beliefs are either insane, or would later have these beliefs challenged. Derleth, meanwhile, not only asserts throughout his story that his explanations are correct, but even confirms so with how the ending plays out, in which the five concepts I listed all spring forth into action in a mere one-and-a-half page finale.

Oh and Hastur screams Tekeli-li, Tekeli-li! now for some reason.

It must be stated that Lovecraft never established firm rules for his pseudo-mythology, and was often more than happy for fellow authors to borrow or use concepts from his stories for their own fiction. This would create contradictions and new lore would be introduced and included, which delighted Lovecraft, who believed that it gave credence to it being akin to a real mythology and loved getting nerdy with his friends; so in due respect, what Derleth was adding to the Mythos on his behalf was him exercising creative freedom that Lovecraft so heavily promoted. If Derleth had kept his additions to his Lovecraft pastiches such as The Return of Hastur, I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you about this, and the contentions that would follow suit.

Derleth, instead of keeping the mythology open as per Lovecraft’s encouragement, would double-down on his newly instituted Cthulhu Mythos, and begin constructing a literary doctrine that future Mythos stories and authors who wished to contribute were expected to follow. To give credence to his beliefs, he began adding Lovecraft’s name onto some of this newly published fiction.

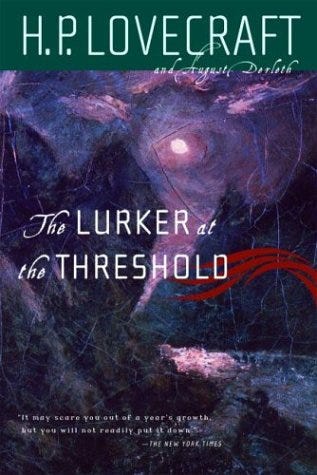

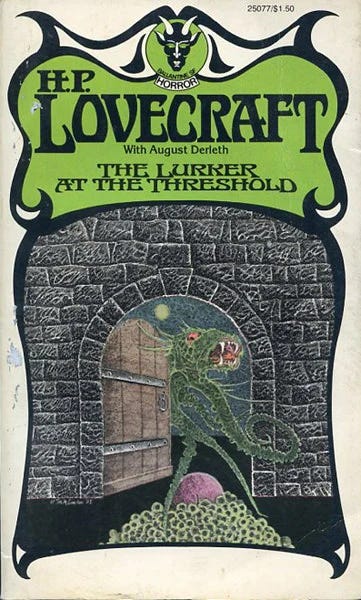

Though it would at first appear that Lovecraft and Derleth wrote this novella together, the truth of the matter is far more duplicitous. Following the small success of four published omnibus’ of Lovecraft’s and other pulp author’s collection of fiction, Derleth would decide to publish what he oxymoronically called a “posthumous collaboration” with Lovecraft, titled The Lurker at the Threshold, released by Arkham House in 1945.

Whilst almost all additions of this novella tout H.P Lovecraft’s name in the biggest and boldest letters, it would be August Derleth who penned a majority of it. According to Lovecraft scholar S.T Joshi, out of the 50,000 words in the novel, on 1,200 were Lovecraft’s own17 (barely over 2%), which were extracted from three unfinished manuscripts that had very little, if anything, to do with each other. Aside from vague scene setting, the plot, characters, descriptions, and dialog were all penned by Derleth, who would originally claim that he had discovered a long-lost, unfinished novel of Lovecraft’s and added some “finishing touches”18.

While a big fan of Lovecraft would most likely notice the conspicuous downgrade in writing quality, Derleth’s move to add Lovecraft’s name is still intellectually dishonest, as a deceased man cannot consent to how his writing can be used, or who can use it. A rather disturbing incorporation in The Lurker at the Threshold is Derleth’s binary concept of the good Elder Gods versus the evil Great Old Ones which, again, is a dichotomy that completely repudiates Lovecraft’s philosophy. By doing this, he was using a dead writer’s name to carry forth his vision for what he believed the Mythos should be about, thus instilling into the reader that the ideas presented are as much Lovecraft’s as they are Derleth’s. The whole novel’s concept was disingenuous at best, and completely deceptive at worst.

The Lurker at the Threshold has been consistently in print since its release, and Lovecraft’s name still vastly overshadows Derleth’s on the cover.

An unfortunate fact about all this is this would not be Derleth’s only foray into using Lovecraft’s unfinished manuscripts for these “posthumous collaborations”. He would go on to publish an additional fifteen stories utilizing this tactic, yet The Lurker at the Threshold is by far the most famous example (I will be going over some of these additional posthumous collaborations in Part III). Though it would inevitably sell over 50,000 copies by its third edition, it was not an immediate success, so Derleth and Wandrei turned to publishing short story collections of various authors outside of themselves and Lovecraft. This included the hardback publication of A.E van Vogt’s serialized science fiction novel Slan in 1946, which would prove to be an overwhelming success and sell 4,000 copies immediately after its first run.

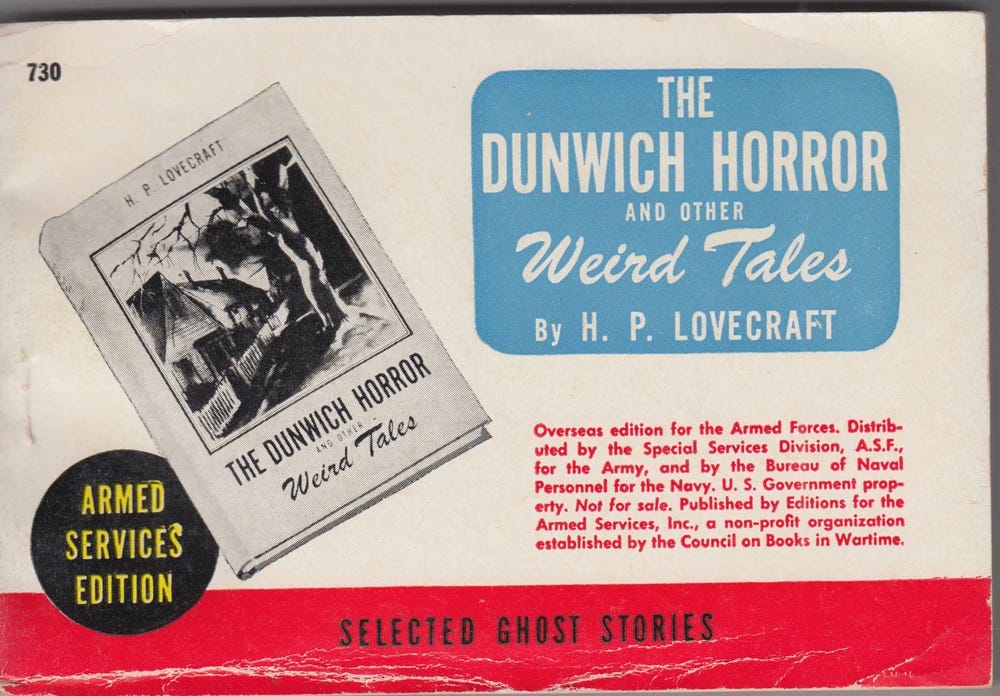

The end of WWII marked the beginning of a transitive phase in American literature. With the rapid advancements in science, the advent of nuclear technology, the start of the Cold War, and foundations of the space race, the public’s imaginations began to ponder over a future that seemed to be keeling towards them faster with each passing day. The gritty, swashbuckling and seemingly juvenile style of the pulps became overshadowed by a sleeker, more sophisticated successor. In just the span of a couple years, science-fiction had begun to dominate the literary landscape.

As Derleth continued to publish hardcover anthologies at Arkham House, during the time when the public was falling under the sway of Asimov and Heinlein’s crisp, foretelling prose in Astounding Stories; a small, yet dedicated collective of writers had already begun to correspond and publish their own literary magazine equivalents.

What these writers published would come to be known as fanzines, and it was here that interest in Lovecraft was not only coming to be respected, but is perhaps the reason fanzines came into existence to begin with.

The Early Fanzines (1920’s-1940’s)

fan·zine

/ˈfanˌzēn/

noun

a magazine, usually produced by amateurs, for fans of a particular performer, group, or form of entertainment19.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Before Substack, before fanfiction.net, before Blogspot and various other writer-oriented websites where one can share their work and interact with appreciators without preamble…there were fanzines.

Throughout his life, Lovecraft was active in the ‘Amateur Journalism’ community, where he procured an extensive coterie of proto-science fiction aficionados and writers. These groups of fans first arose out of pulp magazine letter columns (sections of the magazines dedicated to fan letters, which often featured the letter-writers addresses so that readers could correspond with one another). These individuals would begin interacting with each other in science fiction clubs, conventions, and writer’s associations, where Lovecraft was no stranger to these gatherings. His advocacy for young writers wishing to become published, his kindly, avuncular disposition, and his keen intelligence and experience, quickly made him a welcome and deeply respected member. It is due to these gatherings and correspondences that the early fanzines began to emerge.

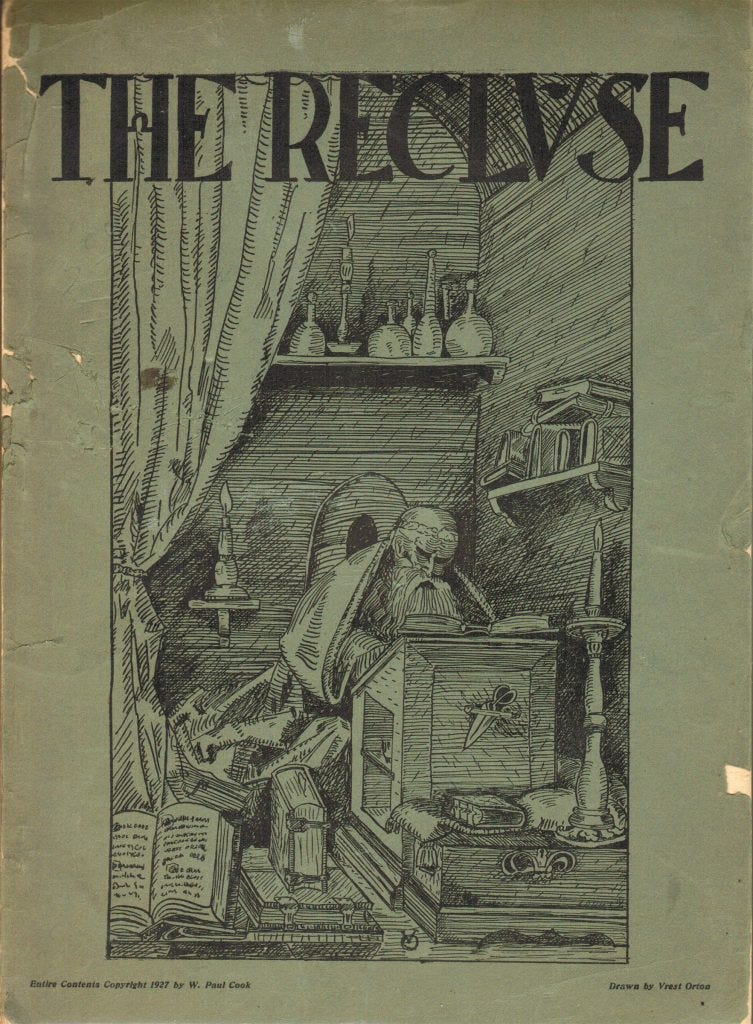

A common consensus amongst collectors of amateur press is that the first known fanzine was Raymond Arthur Palmer’s The Comet, published in 1930 or the Science Correspondences Club. However, some believe there to be an earlier contender, a paleo-fanzine of sorts, with that being W. Paul Cook’s one-shot publication The Recluse, released in 1927, with cover art drawn by Vrest Orton (who would later go on to found The Vermont Country Store with his wife, Mildred).

W. Paul Cook was no stranger to publishing Lovecraft. Upon reading Lovecraft’s juvenilia back in 1917, Cook encouraged the young writer to keep trying his hand at fiction. Many of Lovecraft’s earliest works would be published throughout the 1910’s in Cook’s small-time amateur press magazine The Vagrant, including his pivotal tale Dagon, for which Cook wrote an enthusiastic introduction for20.

Cook’s main focus of The Recluse was publishing essays, doggerel poems, and short stories by authors within Lovecraft’s writing circle: including Lovecraft himself, Clark Ashton Smith, and Samuel Loveman. It is most well-known for first publishing Lovecraft’s seminal analysis Supernatural Horror in Literature21, which would later be republished in Arkham Houses’ The Outsider and Others.

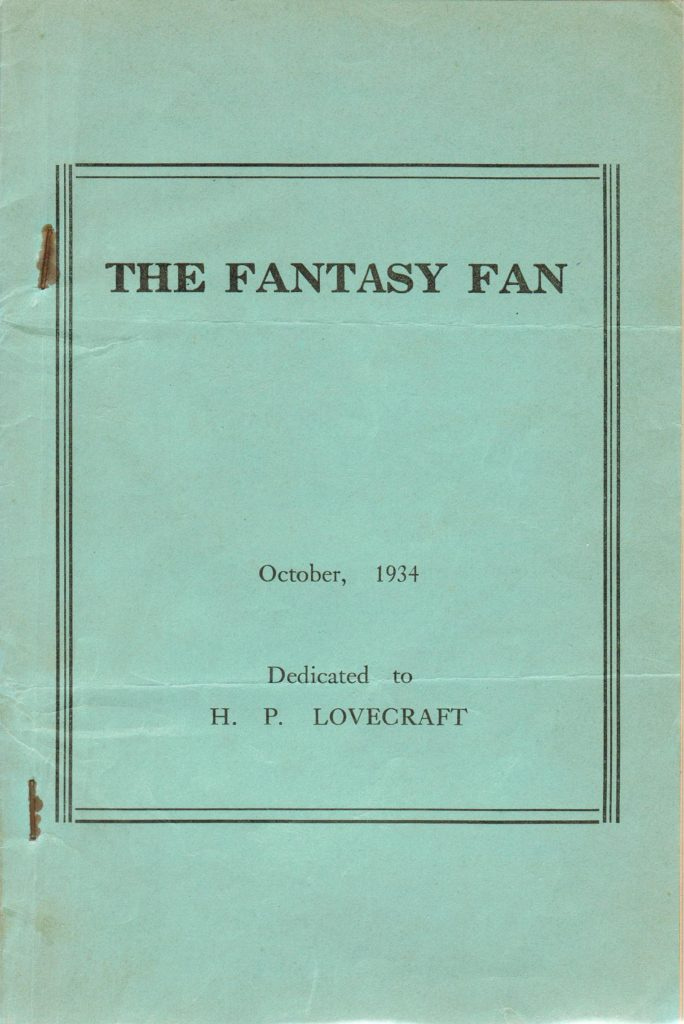

The Recluse was far from being the only fanzine created for Lovecraft’s circle. Charles Hornig’s The Fantasy Fan, which began its publication in 1933 and was started when Hornig was just 17, collected and collaborated with Lovecraft and several other of his writing friends. The Fantasy Fan would later be credited with its representation of then-obscure authors and exposing them to a wider, younger audience.

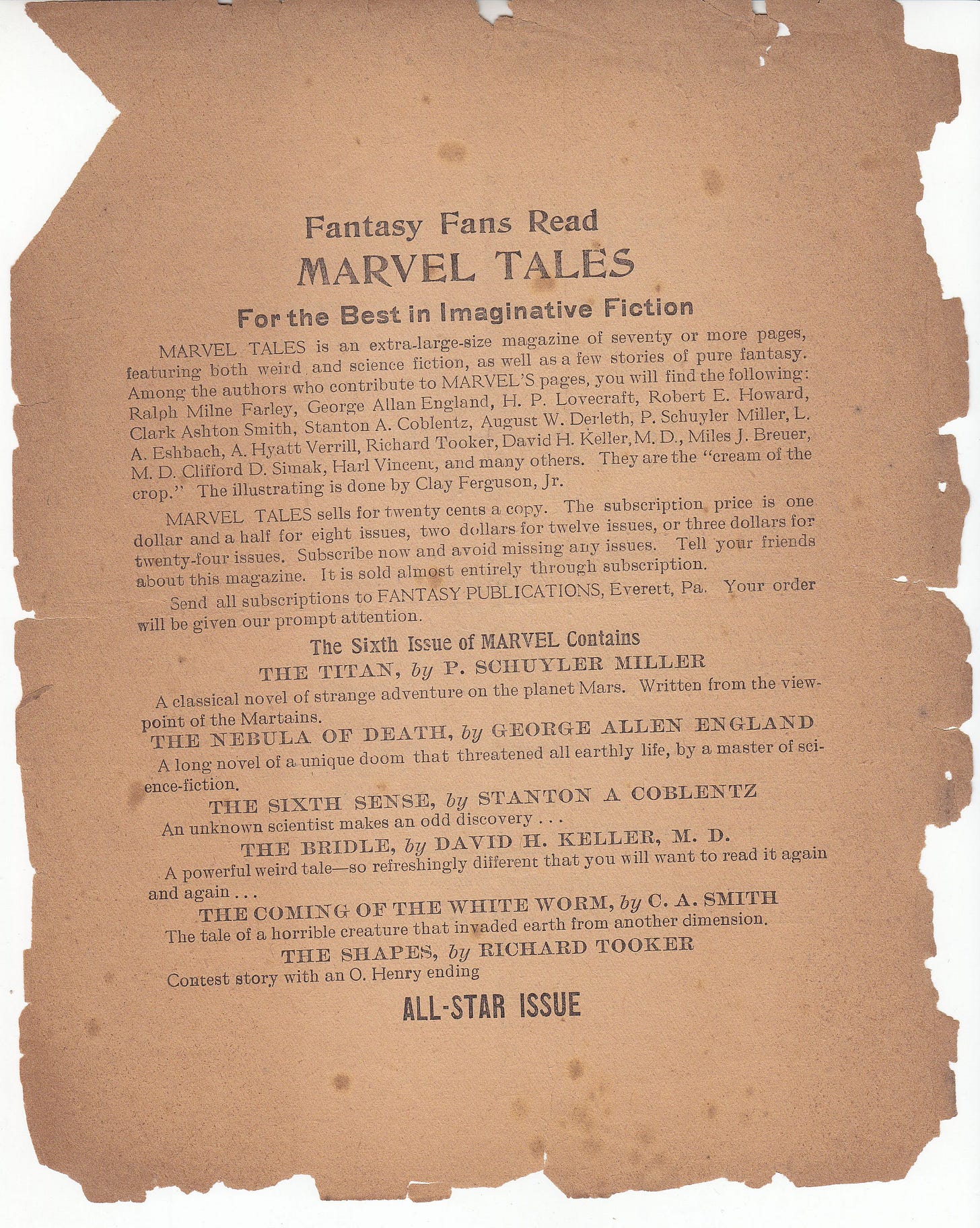

William L. Crawford’s Marvel Tales, which ran from May 1934 to Summer 1935, is another notable fanzine, though the sheer length of each of the five issues (which averaged 70 pages), as well as its more professional layout and creator’s audacious plans for bringing pulp fiction outside of its niche, makes some consider it as a fan-created literary magazine instead. What also differentiated Marvel Tales from fanzines of the time is that it was focused on gaining exposure to a wider audience, with issues being sold rather than circulated for free amongst a small group of fans. Readers of Marvel Tales had the option of paying 20 cents for a single issue, or pledging a subscription for multiple issues starting at $1.50 a month for eight issues22 (which , unfortunately, never came into fruition due to Crawford lacking the finances necessary to continue printing).

Though Marvel Tales has long faded into obscurity, it would hold distinction for being the first known publisher of Robert Bloch and Cordwainer Smith23.

After Lovecraft passed away, fanzines dedicated to his work, manned by his friends and passionate fans, would slowly but steadily, began to crop up.

The earliest example of a post-death Lovecraft-oriented fanzine that I could locate is Cthulhu, of which only one issue was published in 1942 by Douglas C. Webster, a Scottish science fiction editor who had previously run the fanzine The Fantast, which regularly published some of the earliest work of Arthur C. Clarke24 (FUN FACT: One of Clarke’s first published stories was a parody of Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, called At the Mountains of Murkiness, or, from Lovecraft to Leacock. It was published in The Satellite fanzine in 1940).

Aside from a brief article on ZineWiki, and a small scattering of obscure footnotes from a few digitalized 1940’s publications, very little information about this fanzine exists, and it is with unfortunate likelihood that no print of it exists today, as less than 40 copies were ever released25.

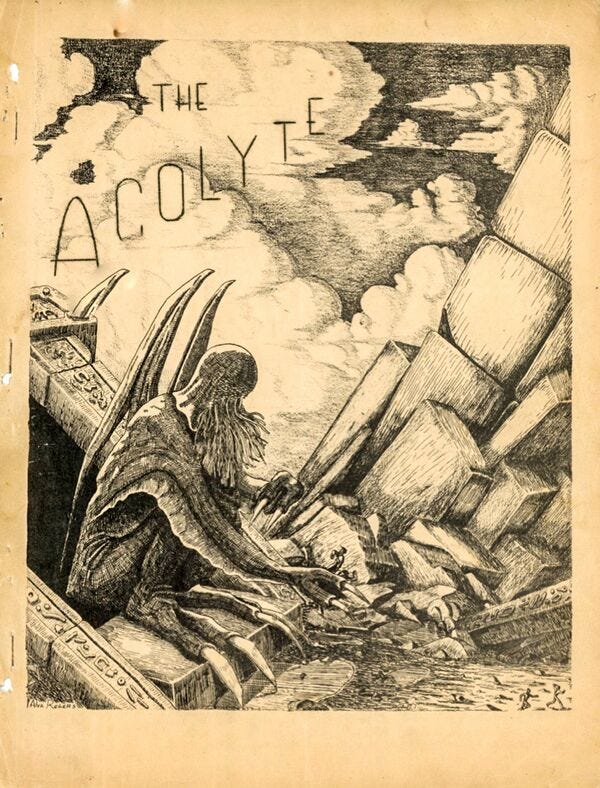

A much more tangible contender, which would also be released the same year, would have to be The Acolyte.

Created in 1942 by Francis T. Laney and Duane W. Rimel out of Clarkston, WA, The Acolyte touted itself as being devoted to H.P Lovecraft and his writing circle, which is not an understatement. Spanning fourteen issues, The Acolyte would not only publish fiction in the vein of Lovecraft, but also the earliest known essays analyzing the author’s work; as well as letter excerpts, unpublished stories and prose, and even the first known map of Arkham. Laney would publish within The Acolyte the very first Lovecraft bestiary, The Cthulhu Mythology: A Glossary, which served as an early “guide” to the Cthulhu Mythos. This essay, and several other writings within The Acolyte, would later be anthologized in a collection of short fiction, essays, and poetry by Arkham House in the book Beyond the Wall of Sleep.

The Acolyte would be nominated in 1946 for a Retrospective Hugo Award for Best Fanzine, though it would not win. That same year, The Acolyte would cease publication. Though a few issues remain missing, most copies have been digitally archived, and can be read for free on fanac.org.

An relatively unknown fanzine that I would like to briefly mention, before wrapping this section up, is Don Wilson’s Dream Quest, published from 1947-1953.

Despite its name being taken from Lovecraft’s The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, and the very first issue bearing a crude drawing of a wingless Cthulhu (and a pterodactyl with a combover), Dream Quest had very little to do with Lovecraft, however the reason I am giving it attention—aside from its referential name and cover art—is that it published the early fiction of a then-17 year-old Lin Carter, specifically; his poetry.

Keep that name in mind, for Lin Carter will be a significant person of interest in Part III.

This is just the tip of the fanzine iceburg, though because I am trying to keep dates chronological, the influential ones that began emerging out of the 1970’s and 80’s will be covered in a later part, which I am very much looking forward to.

And we have made it to the end of Part II! In Part III, we will be marching forward to Arkham House in the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s, Derleth’s close underlings who would adhere themselves to his Mythos, a slew of even more controversial decisions and drama (weird fiction peeps can be catty bitches for real), and (if I can get around to it) the early Lovecraft film adaptations.

Until then, bonum noctis, et mare ditat.

Consider donating to our publication on Ko-fi here!

Wetzel, George T. “Lovecraft’s Literary Executor.” The Lovecraft Scholar, 1983, p. 5. “Sometime between April 5, 1937 and June 23, 1938, he voluntarily relinquished his role in favour of Derleth.”

Smisor: letter, Barlow to Baker, October 12, 1938.

A lake located outside the city of Carcosa, first referenced by Bierce in An Inhabitant of Carcosa.

A symbolic glyph connected to Hastur, first mentioned in Chambers’ The King in Yellow.

Derleth, August, and Donald Andrew Wandrei. Selected Letters III, 1929-1931. Arkham House, 1971, p. 291.

Loucks, Donovan K. “The Cthulhu Mythos.” The H.P. Lovecraft Archive, 1 Jan. 2012, www.hplovecraft.com/popcult/mythos.aspx. "Lovecraft never used the term “Cthulhu Mythos” himself, on rare occasions referring to his series of connected stories as his “Arkham cycle.”

Lovecraft, H.P, and August William Derleth. Essential Solitude: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth. Edited by David E. Schultz and S.T Joshi, Hippocampus Press, 2013.

Lovecraft, H.P, and August William Derleth. Essential Solitude: The Letters of H.P. Lovecraft and August Derleth. Edited by David E. Schultz and S.T Joshi, Hippocampus Press, 2013. “It's not a bad idea to call this Cthulhuism & Yog-Sothothery of mine "The Mythology of Hastur"—although it was really from Machen & Dunsany & others, rather than through the Bierce-Chambers line, that I picked up my gradually developing hash of theogony—or daimonogony.”

Derleth, August. “H.P Lovecraft, Outsider.” River, vol. 1, no. 3, June 1937. Reprinted in Lovecraft Remembered, edited by Peter Cannon. Arkham House, Sauk City, Wisconsin, 1998, pp. 410–414. This essay contains the earliest known mention of the Cthulhu Mythos moniker.

Hanley, Terence E. “The Fungi from Yuggoth.” The Fungi from Yuggoth, Tellers of Weird Tales, 1 Oct. 2018, tellersofweirdtales.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-fungi-from-yuggoth.html.

Farnese, Harold. Letters to August Derleth. State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

Schultz, David E. “The Origin of Lovecraft’s ‘Black Magic’ Quote.” Crypt of Cthulhu, no. 48, 23 June 1987.

Derleth, August and James Turner. Selected Letters IV, 1932-1934. Arkham House, 1976.

Lovecraft, H. P., and S. T. Joshi. “H. P. Lovecraft’s ‘Sunset.’” Lovecraft Annual, no. 13, 2019, pp. 102–10. JSTOR.

Price, Robert M., et al. The Hastur Cycle: 13 Tales of Horror Defining Hastur, The King in Yellow, Yuggoth, and the Dread City of Carcosa. Second ed., Chaosium, 2014, p. 248

Morales, Joseph. “The Family Tree of the Gods.” Cthulhu Files, 2022, cthulhufiles.com/family_tree_of_the_gods.htm.

Joshi, S. T. H.P. Lovecraft: A Comprehensive Bibliography. University of Tampa Press, 2009. "In some instances Derleth incorporated actual prose passages by Lovecraft into his stories. The Lurker at the Threshold (a 50,000-word novel) contains about 1,200 words by Lovecraft, most of it taken from a fragment entitled “Of Evill Sorceries Done in New England”... the balance from a fragment now titled “The Rose Window”."

B., Arthur. “Derleth-Er of Two Evils.” Jumbled Thoughts of a Fake Geek Boy, 28 Aug. 2021, fakegeekboy.wordpress.com/2016/12/01/derleth-er-of-two-evils/. "Derleth claimed that The Lurker At the Threshold was an unfinished novel he had put the final touches to, but this very clearly isn’t the case if you look at the source material he was drawing on."

Oxford Languages definition.

“The Vagrant.” ZineWiki, zinewiki.com/wiki/The_Vagrant.

“Publication: The Recluse, 1927.” Internet Speculative Fiction Database, 25 Nov. 2013.

“Fantasy Fans Read Marvel Tales.” The Phantagraph, 1935. https://fanac.org/fanzines/Phantagraph/Phanta11-ic.html?

MacDermott, Aubrey. Aubrey MacDermott on the Origins of Fandom. https://fancyclopedia.org/Aubrey_MacDermott_on_the_Origins_of_Fandom. “Crawford also has the distinction of being the first publisher of Robert Bloch and Cordwainer Smith”

“Publication: The Fantast, April 1942.” Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

“Cthulhu.” ZineWiki, zinewiki.com/wiki/Cthulhu.

Really well done! This series is probably going to be one of the most comprehensive sources about the history of post-Lovecraft fiction! I was particularly interested in the parts about Farnese and his compositions of Lovecraftian music. That in and of itself would be a great topic for a future post!

I am loving this series! Part 2 was just as fascinating and detailed as part one. I don’t know much at all about the development of the mythos after Lovecraft’s death and have learned so much. Your articles are brilliant!