The Legacy of Lovecraft: How the Mythos Emerged from the Shadows, Part I

The complicated and controversial background of a pulp author's rise to fame, part 1.

Credit goes to Ethan Sabatella for helping with the title of this essay.

Introduction

As I stated in Part I of my introductory post to the man’s works, Howard Phillips Lovecraft lived and died in relative obscurity, with his works often falling out of print after being published for a single issue in Weird Tales (with the exception being The Shadow Over Innsmouth, which was released by the Visionary Publishing Company as a novella in 1936, the only story of Lovecraft’s to be published in such a format in his lifetime). Despite this shortcoming, Lovecraft was able to amass a group of fellow writer friends within his short life, with whom he would partake in collaborations, the writer’s frequently referencing each other’s concepts and characters in their published literature. He would also serve as a mentor for a handful of aspiring writers who had come across his stories, serving as a respected guru for individuals who would go on to become renowned authors themselves.

Both of these examples of establishing coterie within the horror writing scene would ultimately serve as the catalyst for his claim to the Pulp Horror throne, though this title would only be crowned posthumously after his death, following a decades-long endeavor on the behalf of friends who worked to place his fiction in the limelight. The road to Lovecraft’s literary stardom, however, is one that involves an intriguing cast of characters, unexpected twists, equal parts tragedy and triumph, and the birth of the Mythos we have all come to be familiar with; all spanning over a period of several decades before the long-deceased writer received his first breakthrough into the pop culture sphere.

This is, to the best of my ability and research, the story of Lovecraft’s legacy and how he became elevated to the status as the Godfather of Cosmic Horror.

~This was originally intended to all be covered in a single post, but due to the amount of history and complexity I want to cover on the topic, in order to provide as comprehensive a timeline as possible for how Lovecraft became a popular and beloved horror figure, there is going to be multiple parts.~

The funeral of Howard Phillips Lovecraft, much like the now-renowned Edgar Allen Poe he cited as one off his greatest influences, was a solemn affair attended by no more than four people (some sources are more conservative and merely say two, one of which included his Aunt Annie). He had passed away no less than three days prior, with a pithy obituary published the following day in a local Providence newspaper. The whole experience, from his death to being lain under his family’s plot, all occurred in the span of four days1.

His many friends would not discover his passing until weeks later, and when they did, they began coming up with ways to properly honor him and cement his legacy.

The Beginnings of Arkham House

The name ‘August Derleth’ may ring a few bells, particularly if you are:

A nerd

Deeply entrenched in the table-top roleplaying scene (Chaosium’s Call of Cthulhu, anyone?)

A huge fan of classic American pulps and science fiction

A researcher of Lovecraft’s background or anyone else involved in his writing circle.

If this is your first time hearing this name, fear not, for I shall do my best to shed some light on this individual.

August Derleth extendedly contributed for magazines, scholarly journals, and various small-time publishing houses throughout the early and mid-20th century. A prolific writer, Derleth is credited with penning over 150 short stories, 100 books, and thousands of articles and reviews2. His creative writing encompassed multiple genres including horror pastiche, cosmic horror, whodunnits, mystery novels, children’s literature, science fiction, non-fiction, and a long-branching saga about the trials and tribulations of a cluster of small Midwestern villages (The Sac Prairie Saga)3, which would later be praised by Sinclair Lewis in Esquire4.

Despite his extensive oeuvre, Derleth is nowadays known mainly for one thing: promoting and preserving the works of obscure pulp fiction authors, with his most famous and acclaimed example being Howard Phillips Lovecraft. In 1939, upon learning of Lovecraft’s death and after various failed attempts of getting Lovecraft’s writing republished, August Derleth and fellow weird fiction author Donald Andrew Wandrei founded Arkham House, a small publishing company dedicated to creating hardback anthologies of Lovecraft’s work. Derleth and Lovecraft frequently corresponded in letters throughout the late 1920’s until the latter author’s passing, with the two quickly becoming close friends (fun fact: the fictional character of Comte d’Erlette, a grimoire author referenced in The Shadow over Innsmouth and The Haunter of the Dark, is based on August Derleth, himself5).

Arkham House would release various high-quality albeit expensive collections of Lovecraft’s writing, starting with The Outsider & Others in 1939, a substantial anthology of Lovecraft’s short stories that was the very first of its kind. Throughout the 1940’s, Arkham House would release several additional anthologies of Lovecraft’s writings, as well as the works of other contemporaries whom Arkham House helped establish as literary masters; including Ray Bradbury, Frank Belknap Long, Robert Bloch, and several other pulp authors whom Derleth and Lovecraft had become acquainted with. In addition to this, Arkham would also rerelease the works of authors whom Lovecraft was influenced by, such as Algernon Blackwood and Sheridan Le Fanu6.

With an extensive catalog and passion for saving his friend and others from being mere footnotes in pulp horror history, fate could have easily played out not only in Lovecraft’s favor, but in Derleth’s as well, cementing him as a figurehead in modern American literature for his accomplishments as a literary preservationist, essayist, and writer; and though he is often credited for establishing Lovecraft as a pioneer of the macabre in the vein of Poe and Machen, Derleth’s reputation in the 21st century has been greatly scrutinized and negated with time.

There are several reasons for this undoing, and it will play significantly with how the Mythos would develop and be perceived by fans for decades. For as much as he contributed to Lovecraft’s immortalization, Derleth would also make several mistakes, questionable decisions, and restructurings of the Mythos to the point where many have deemed it unrecognizable to Lovecraft’s original ideas. I will go over this in greater detail later on, as I need to start with what is often an overlooked piece of Lovecraftian scholarly history.

The first great err that Derleth committed, and one of his most impactful ones, would be his treatment towards Robert Barlow.

Robert Barlow

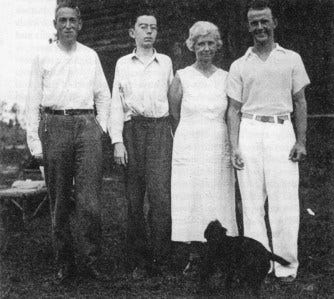

Robert Hayword Barlow was born on May 18th, 1918 in Leavenworth, Kansas, though due to his father, Everett Barlow, being conscripted in the American Armed Forces, the family moved frequently. In 1932, the family would permanently locate to DeLand, Florida, following Everett’s medical discharge, where they would establish a lakeside residence. It was during this time in Barlow’s life when he began corresponding with H.P Lovecraft.

At age 13, Barlow was a precocious, intelligent boy with a passion for becoming an established writer. Due to his unorthodox childhood, Barlow had self-educated himself on the works of various authors, though his favorites were those who wrote for the pulps. He wrote, with great frequency and zeal, to both Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard7, the latter whose works include Conan the Barbarian and Solomon Kane. Lovecraft and Barlow rapidly became friends, and the two collaborated on several stories together in the mid-1930’s, many of which remained out of print until the 90’s. Their most famous collaboration is The Night Ocean (1936), a hauntingly beautiful tale that showcases the talent of the teenaged Barlow and a delicate side of Lovecraft that had appeared very little in his previous works.

Lovecraft would make extended trips to the Barlow residence several times during the final few years of his life, often staying for several months at a time, in which the two would write their stories together, discuss fine literature, take various walks around the lake, and even constructed an elaborate prank which included ghost-writing a parodical short story, in which various Weird Tales authors—pardon my French—beat the ever-living shit out of each other8, with Barlow mailing it to all the authors featured in the tale (it is honest-to-god hilarious—you’ve gotta read it). Barlow would later visit Lovecraft in Providence in the Summer of 1936. The two would travel frequently, along with a fellow Lovecraft protege named Kenneth Sterling, up and down the East Coast to towns such as Salem and Marblehead, both of which were greatly influential to Lovecraft9.

Barlow would immediately return to Providence the following Spring, upon receiving a telegram from Lovecraft’s aunt that the author had passed away. In the throes of grief, Barlow would be shocked to discover that Lovecraft had appointed the 18-year-old as his literary executor. Lovecraft’s aunt, Annie Gamwell, would establish a contract which would allow Barlow to inherit all of Lovecraft’s manuscripts, with the earnings from stories he re-published to be given to Gamwell, though Barlow would receive a small commission for his efforts1011.

It was almost immediate that after the contract was signed, that August Derleth would begin his attempts at seizing control of executorship.

Derleth would first approach Barlow with the claim that the contract he had signed was null, on the stance that Lovecraft had given permission to Derleth in 1936 to publish a collection of his short stories (which I have a hunch would become The Outsider and Other Stories). When Barlow wasn’t convinced, Derleth spun another false yarn, this time saying the contract was invalid due to Barlow being a minor, and that Lovecraft had appointed a literary agent the previous year. While the appointing of the literary agent was in fact true, this establishment would not have voided Barlow’s contract, as the posthumous designation made by a deceased author’s family would be respected if the contract was validated (which in this case, it was). The third and final argument (that we know of) that Derleth begat was that Annie Gamwell, Lovecraft’s aunt, due to supposed Rhode Island law, could not legally run Lovecraft’s estate, claiming that Sonia Greene, his widow, could only act on such terms. This, however, completely contradicts the state’s law, which actually governs that the deceased’s will cannot be revoked following marriage12.

Though Derleth portrayed himself to Barlow as a fatherly figure who was looking after the young man’s wellbeing and supposedly educating him on his (lack of) legal rights, his conduct behind-the-scenes conveyed the opposite. Derleth, more than aware of Barlow’s homosexuality (which the youth had kept hidden from Lovecraft during their friendship), would consistently slander him in various letters to correspondences and writers in the pulp scene, though he was subtle with his choice of words13. Donald Wandrei, Derleth’s best friend, developed an ever deeper dislike of Barlow, believing that the teenager had stolen Lovecraft’s manuscripts. When Derleth and Wandrei founded Arkham House together in 1939, they would both insistently encourage other respected pulp writers, such as Clark Ashton Smith and Frank Belknap Long, to shun Barlow. The result of their targeted harassment would deem Barlow the black sheep of the writing circle, and would inevitably be pushed out of the field14. What adds insult to injury is that Barlow has chosen to resign his executorship to Derleth just the previous year, thus granting Derleth his most desired wish.

Barlow’s life from here would take an interesting—albeit depressing—turn. Fascinated by the culture of Mesoamerica, he would eventually receive his Bachelors degree in Anthropology, and permanently locate to Mexico and join the staff of Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, where he would begin teaching Nahuatl15 and Mexican History. He would become the Chairman of Anthropology at Mexico City College in 1948, where he would translate Mayan codices and do extensive research on Indigenous Mesoamerica.

Though a deeply accomplished individual who was acclaimed by his scholarly peers, Barlow experienced long bouts of severe depression, writing to a friend that he felt his life would not prolong itself. On New Years Day of 1951, Barlow, fearful that his homosexuality would be exposed by a fellow student, would lock himself in his bedroom, ingest a bottle of Seconal, and pin a letter to his door which read in Mayan “Do not disturb me. I want to sleep a long time.”

His body would be discovered the following day. He was only 32 years old.

(Intriguingly, William S. Burroughs, who was a student under Robert Barlow in 1950, would later pen a letter to Allen Ginsburg, in which he briefly described Barlow’s death).

Though he was cast out of the Lovecraft circle, Barlow would later come to be known for two extraordinary things. The first were his donations of many of Lovecraft’s original manuscripts, various letters, and juvenilia to Brown University. Now resting in the John Hay Library, it is the university’s most popular collection16.

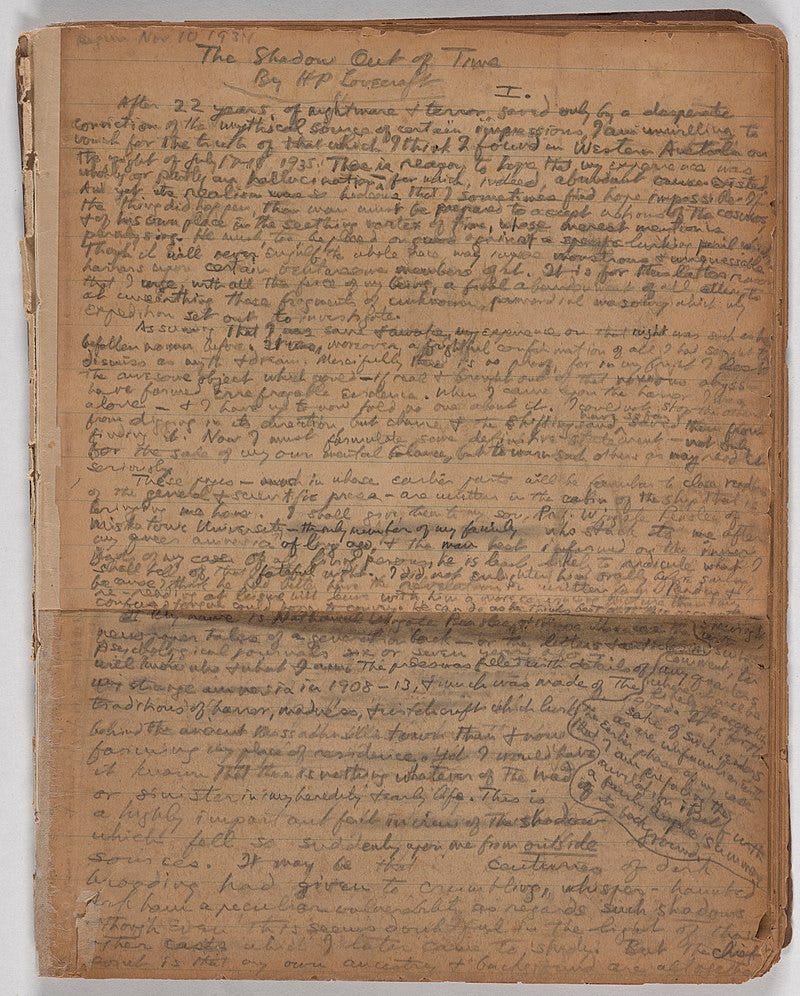

The second was his transcription of The Shadow out of Time, one of Lovecraft’s most seminal works. Barlow would transcribe the 25,000+17 worded novella verbatim in the Summer of 1935, after a visiting Lovecraft had shown him the manuscript. Though the novella would be published in Astounding Stories in 1936, it was a truncated version of Lovecraft’s original story, and included several editing errors, much to Lovecraft’s displeasure.

Barlow kept the original transcript until befriending June Ripley, a post-graduate student who studied Nahuatl. Barlow bestowed Ripley with the transcript months before committing suicide, though this information would not be known for several decades, and the original version of The Shadow Out of Time would be monikered “the lost manuscript”. After Ripley’s death in 1993, the transcript would be sent to Brown University the following year, faded with time but still faintly legible. The transcript included numerous word and paragraph differences, as well as text omitted from the published version. Its discovery is considered a holy grail in Lovecraftian scholarship, and The Shadow out of Time can now be read exactly as Lovecraft originally wrote it18.

Whilst this concludes my section regarding Robert Barlow, I highly recommend further reading on this individual, as I firmly believe he is one of the most fascinating and tragic characters in the entire Lovecraft circle. While there is currently no complete biography of Barlow’s life, I highly recommend reading Marcos Legaria’s L'Affaire Barlow…, which delves deeper into his impact on Lovecraft’s legacy.

Thus we come to a close for Part I. In Part II, we will be exploring more into the role of Arkham House, and how Derleth would begin to forever change the course of the Cthulhu Mythos for the good, the bad, and the…well, I’ll let you be the judge.

Until then, bonum noctis, et mare ditat.

Lovecraft’s official day of passing was March 15th, 1937, aged 46. His obituary was published March 16th, and his funeral occurred that Thursday of the same week, on March 18th.

“Derleth, August, 1909-1971.” Wisconsin Historical Society, 3 Aug. 2012, www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1941. "He is often regarded as Wisconsin's most prolific author, with more than 100 books, 150 short stories and several thousand articles to his credit."

“Summary Bibliography: August Derleth.” Isfdb.org, The Internet Speculative Fiction Database, www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/ea.cgi?825. (This is, to my knowledge, the most comprehensive bibliography of August Derleth to date, though due to Derleth’s prolific career, it is not possible to catalog his entire collection).

Wright, Boyd, and Lloyd Currey. “Results for: Masters of Fantasy and Horror: August Derleth.” L. W. Currey, Inc., www.lwcurrey.com/searchResults.php?action=catalog&category_id=20292. "His series of the 'Sac Prairie Saga,' most of them novels, is already formidable. He has not trotted off to New York literary cocktail parties or to the Hollywood studios. He has stayed home and built up a solid work that demands the attention of anybody who believes that American fiction is at last growing up … He is a champion and justification of regionalism."

Contributors to The H.P. Lovecraft Wiki. “Comte d’Erlette.” The H.P. Lovecraft Wiki, Fandom, Inc., lovecraft.fandom.com/wiki/Comte_d%27Erlette. “The title of the character is inspired by the ancestral form of Mythos author August Derleth’s name and a nickname frequently used for him by H.P Lovecraft in his correspondence.”

Currey, Lloyd. “Arkham House / August Derleth Archive.” L. W. Currey, Inc.., www.lwcurrey.com/arkham-house-archive-private.php.

Vick, Todd B., and Bobby Derie. “The Two Bobs: Robert E. Howard and Robert H. Barlow by Bobby Derie.” The Two Bobs: Robert E. Howard and Robert H. Barlow by Bobby Derie, On the Underwood No. 5, 14 Dec. 2017.

Richardson, Deuce. “Robert H. Barlow -- 70 Years Gone.” DMR Books, 3 Jan. 2021, dmrbooks.com/test-blog/2021/1/2/robert-h-barlow-70-years-gone. "While he was visiting the Barlows, HPL and RHB cooked up the biggest prank in the history of the Lovecraft Circle: "The Battle That Ended the Century". Set in the year 2000, "Battle" is the tale of a titanic boxing bout between Two-Gun Bob, the Terror of the Plains (REH), and Knockout Bernie, the Wild Wolf of West Shokan (Bernard Dwyer). Fun was poked at all and sundry, including HPL himself, with in-jokes packed into every sentence."

La Farge, Paul. “The Complicated Friendship of H.P Lovecraft and Robert Barlowe.” The New Yorker, 9 Mar. 2017. “The next summer, Barlow went to Providence...When the two of them took a trip to Salem and Marblehead, towns which Lovecraft had mythologized in his fiction, another of Lovecraft’s young protégés, a sixteen-year-old named Kenneth Sterling, who was about to enroll at Harvard, came along, too.”

George Smisor: contract between Robert Barlow and Mrs. Gamwell, signed March 26, 1937

Wetzel, George T. “Lovecraft’s Literary Executor.” The Lovecraft Scholar, 1983, p. 3-5

Wetzel, George T. “Lovecraft’s Literary Executor.” The Lovecraft Scholar, 1983, p. 4-5

Legaria, Marcos. L’Affaire Barlow: H.P. Lovecraft and the Battle For His Literary Legacy. Bold Venture Press, 2023.

Schultz, David E, and S.T Joshi, editors. To Worlds Unknown: The Letters of Clark Ashton Smith, Donald Wandrei, Howard Wandrei, and R.H Barlow. Hippocampus Press, 2023.

The language spoken by the Aztecs, and the native language of the Nahua people.

“Influence of Anxiety: Lovecraft, Bloch, Barlow, et Al.” Brown University Library, Brown University, 14 July 2015, library.brown.edu/create/lovecraft/intro/. "Shortly after Lovecraft’s death in 1937, Barlow, acting as his literary executor, delivered the first donation of manuscripts and correspondence to the John Hay Library. The H. P. Lovecraft Collection now includes extensive holdings of manuscripts, letters, editions of Lovecraft’s works in 20 languages, periodicals, biographical and critical works, and numerous collections of manuscript and printed materials..."

The exact word-count is in fact 25,323 words, but hey who’s counting?

Mysterious Lovercraft Manuscript, Brown University Library, library.brown.edu/friends/publications/AFspring95/Lovecraft.html.

Fascinating thank you!

So interesting to read about Robert Barlow. Such an intriguing character - someone should write a novel or make a film about his life.